Best Practice Guides

VIEW & PRINT PLAN FOR NATURE LEAFLET HERE

Plan For Nature

Why should I farm for nature?

Agricultural Benefits: Looking after the soil, water and habitats on your farm can yield many benefits. For livestock, a mosaic of healthy habitats will provide better shelter and shade, cleaner water and a more varied diet. Healthy soils will mean better crops and lower costs. Future agri-environment schemes will mostly likely reward those farmers who deliver better environmental outcomes, so by managing nature well on your farm, you may enhance future farm payments. Best of all though, by farming for nature you will leave the land in the best possible condition for future generations.

Ecological Benefits: Habitats that are in good condition are key for our native flora and fauna, with habitat loss one of the major causes of our biodiversity crisis. Well-managed hedgerows, flower- rich grasslands and wetlands, clean watercourses and healthy soils are the building blocks for a thriving ecosystem. A healthy range of habitats on our farm means a better range and diversity of shelter, food and water sources for our wildlife.

Climate Benefits: Having a good range of healthy, well-functioning habitats – hedgerows, trees, more natural grasslands, wetlands – on the farm will help to capture and store carbon, thus mitigating against climate change. These habitats, if managed appropriately, may also be used to build ‘resilience’ and counter some of the negative impacts of climate change – fire, flood and drought for example – which are happening more often.

How do I farm for nature?

Every field and every farm is different and nobody knows the land and its management history as well as the farmer. However, none of us know it all, so talk to lots of people – neighbours, other farmers, your NPWS ranger or heritage officer, a local scientist – ask for their opinion and write down any good ideas they might have. Go on other farm walks or nature walks – they provide a great opportunity to learn first-hand from others.

A good first step is to do your own ‘mini-research project’ on your farm. Start by drawing a map – jotting down notes on your ‘Area Aid’ map maybe or, better still, sketch a rough outline of your farm (or a field within it) on a blank sheet and add in colours, drawings and notes. Draw in the main habitats – hedgerows, woodland, scrub, trees, wetland areas, open water, meadows, improved pasture. Add any monuments, built structures and field names.

Next, observe your land over the course of the four seasons. Understanding where you are starting from is fundamental to any process of planning ahead, so consider what habitats and species your land currently supports (or used to support). Try to walk the land once a week or fortnight and take a few notes on what you see – what’s in flower (take a picture if you don’t know the name), where and when? Do you notice any butterflies, birds or mammals? Identifying the best areas for biodiversity on your farm is important – it’s much better to protect these habitats before you go creating new ones! Also, look at your neighbour’s land – what’s there, is it different, why?

Record current management on your land. What stock are where, when, how many? When are animals housed, if at all? What fertilisers, slurry, farmyard manure or chemicals are applied? What crops are planted, when and where? Has the current management regime been in place for a long time or is it more recent? Can you change it easily?

Next, think about what you would like your field/farm to look like in ten years. Wider hedgerows and/or new ones? A meadow here or a copse of trees there? What about a pond? Try to think about connectivity, linking habitats together (within your farm and possibly with your neighbours). Think about the whole year – while food may be plentiful in Summer, are your habitats good at providing food in Spring and Autumn for pollinators and birds? Think long-term – the habitats you retain, restore or create today will support nature and give pleasure to your children and grandchildren long after you are gone, as they sit beside a pond you made, or under an oak copse you planted.

When planning, think in the following order: retain, enhance, create. Hang on to what you have and try to improve it – it’s the most efficient approach. Then explore what further habitats would suit your farm, making sure you are not replacing valuable existing habitats by doing so – don’t cover your species-rich grassland with trees for example!

Finally, consider what management changes you may need to make to realize your plan. Do you need more stock or less? Do you need new fences or boundaries, watering points, farm equipment or animal housing? If you aren’t farming yourself, do you know a trustworthy farmer to help manage the farm in the way that you want? When it comes to management changes, think evolution, not revolution. Learn as you go, observe the impact of your actions and adapt accordingly. Be realistic – some areas may need be managed more intensively for the farm to be viable.

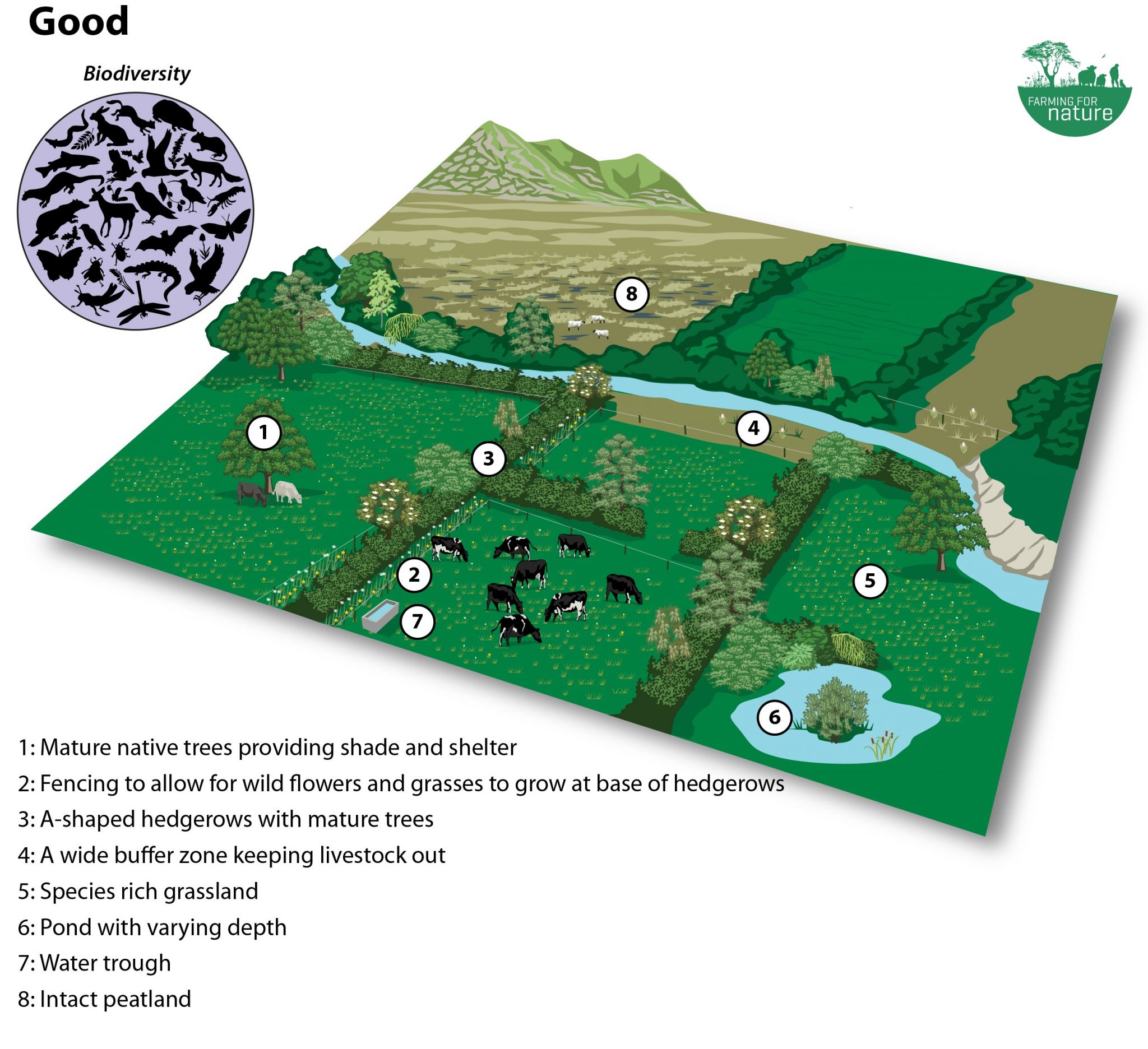

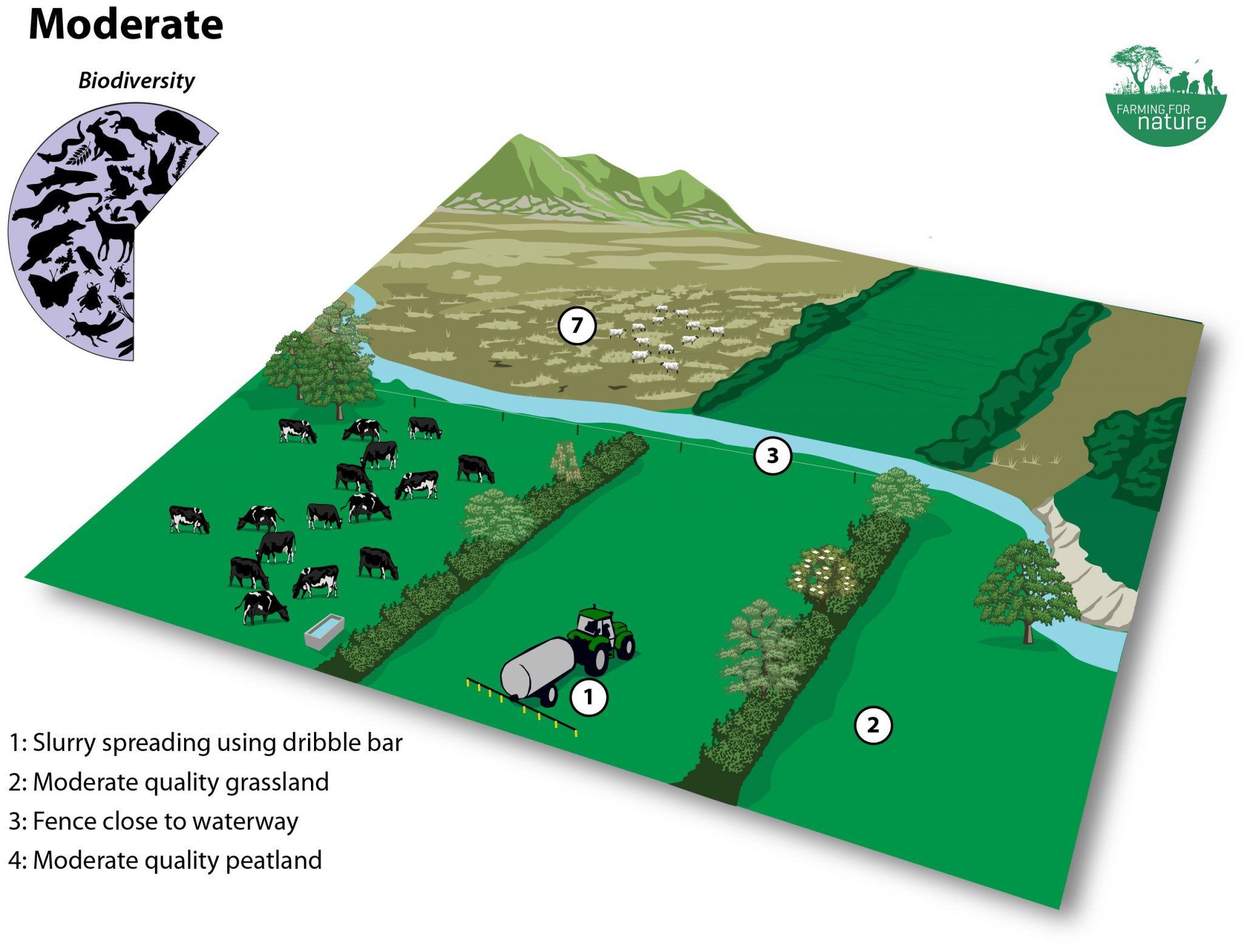

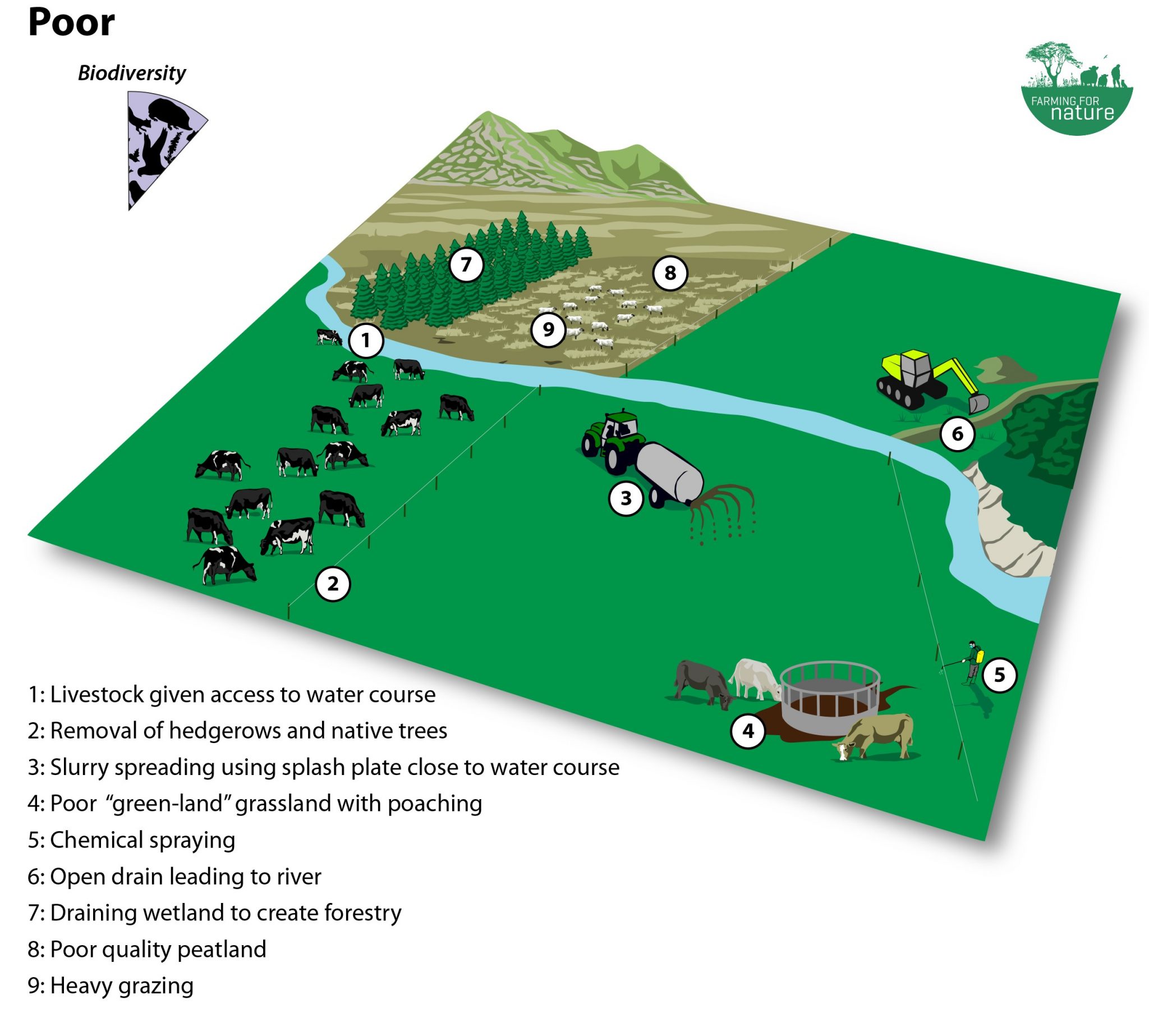

What does a well-managed farm with lots of biodiversity look like?

Some tips for starters:

- You don’t need to do everything all at once, you can add to your plan season by season, or year by year.

- Start with some easy wins. Consider providing a mini-sanctuary for key species you wish to attract to your farm. This could be in the form of beetle banks, earth banks for solitary bees, nest boxes for barn owls, nesting cups for swallows and house martins, hibernation spots for bats etc. Or you could plant seed-bearing plots for yellowhammers, goldfinches and linnets, pile timber and dead leaves for insects and hedgehogs, leave long grass for moths and hares etc. Simple ideas can do wonders and build confidence!

- For a species-rich grassland, start with areas that already have some diversity of plant species – usually ‘neglected’ or difficult areas which haven’t been reseeded or fertilised for some time. Rest these areas during the main flowering season (usually May-July) so they can flower and set seed, then graze or mow from late summer onwards to reduce competition and lower the nutrient load in the field.

- Planting or enhancing an existing hedgerow with native and diverse species is also a great place to start. Allow the hedgerow bases and other field margins to flower and set seed before cutting – this may require some fencing, consider 2m out from the hedgerow base, during the main flowering period (May-July).

- Fence off at least a 3-metre buffer strip for rivers, 2-metre for streams to prevent nutrient run-off into watercourses. These can be cut or grazed in autumn to encourage more diverse growth.

- If you are able to create some new habitats on your farm, remember that they are more likely to be used if they are close to, or connected with, existing habitats.

- Another simple task is to create a pond of various depths. If doing so, try to choose a location which is new rather than one which is already supporting wetland wildlife.

- Another nice idea is to create a specific native wildflower pollinator plot for bees, butterflies, moths and hoverflies so that there are always flowers in bloom between February and October.

Avoid

- Nature works best when it not ‘over-managed’, so don’t be too neat and tidy with your management. Try not to mow/graze grasslands in early summer. Consider leaving hedgerows for 3-5 years before cutting.

- Do not destroy one natural habitat to create another – for instance if you have wetland area and overwintering birds or nesting snipe, don’t drain it to create a woodland.

- Do not spread slurry and fertilizers on ‘unimproved’ natural pastures, particularly in the vicinity of watercourses; this will impact negatively on the invertebrates in the soil and water and on the wild flowers.

- Avoid changing what currently works – some crops you grow may attract farmland birds like lapwings – consider your crop management to allow them to feed and nest instead of changing your crops.

- Reduce or completely avoid the use of toxic rodenticides; these can inadvertently lead to the death of owls or other non-target species. There are alternatives which can be very effective.

- Reduce pesticide and herbicide inputs or stop them completely if you can. Avoiding spraying road frontage (its ugly!), field margins, wetlands and other natural habitats.

- Reduce tilling of your soils to encourage your soil microbes and worms to increase.

Looking for more information for your farm, search by

Where to Start Sector Habitat Season FAQs

More resources