Best Practice Guidelines

VIEW & PRINT AS GRASSLANDS LEAFLET HERE

Managing species-rich grasslands (pastures & meadows)

Species-rich grasslands are generally ‘unimproved’ or ‘semi-natural’ grasslands which have been farmed without the application of significant quantities of nutrients (chemical fertiliser, slurry) or herbicide. Typically, these grasslands have not been ploughed or re-seeded in recent times. As a result, they support a variety of wildflowers and grasses that cannot thrive in more intensively-managed swards. This variety of plant species in turn attracts other wildlife such as insects, birds and small mammals. Farming practices such as grazing or meadowing, when done properly, are essential to the continued ‘species-rich’ status of these grasslands as, once these areas are intensified or abandoned, the diversity and abundance of species falls significantly and it is usually very difficult and costly to restore them.

Why conserve species-rich grasslands?

Agricultural Benefits: More varied herbage can be beneficial to grazing livestock as it provides them with a greater variety of vitamins, minerals and nutrients than ‘improved’ grasslands which support only a handful of species. Having a diverse sward, which in turn supports a diversity of insects and other invertebrates, may offer benefits of natural pest control (e.g. ladybirds which eat aphids, birds which eat caterpillars etc), reducing the need for artificial (and costly) treatments. A diverse sward with different rooting depths may also improve resilience against drought. Hay taken from species-rich areas is valuable for restoring degraded grasslands and is often in-demand. Beef and other meat produced on species-rich grasslands lends itself well to niche marketing efforts – the market for species-rich produce in Ireland is ripe for development, being limited to small-scale producer groups. Finally, with a move towards ‘result-based’ Agri-environment schemes, more species may mean more money in the farmer’s pocket!

Ecological Benefits: Where they remain, old hay meadows and semi-natural (or ‘less intensively farmed’) grasslands are some of the most species-rich habitats in Ireland, hosting a wide range of our native plants including a rich array of orchids. These areas are, in turn, excellent habitats for invertebrates, farmland specialist birds (e.g. skylark, yellowhammer, curlew and, in a few rare cases, the corncrake) and small mammals that rely on these seed-rich habitats for food, especially through the winter. Semi-natural grasslands also support healthy soils, with a fabulous array of soil micro-organisms, including beneficial bacteria and fungi. These soils can store more water due to their good ‘open’ structure, and can also grow and support a wide range of healthy plants.

Climate Benefits: Permanent pasture is good at storing carbon – in contrast to reseeded grasslands which lose a lot of carbon through periodic soil disturbance. Carbon stores are very high in semi-natural grasslands associated with traditional cattle grazing in low stocking densities. Having a multitude of different species in a sward also confers greater resilience for farmers in the face of climate change. Some species have deeper roots, and can survive dry periods – this was clearly borne out in the recent long dry spell of 2018, when aerial photographs showed semi-natural grasslands staying relatively green during the drought compared with species-poor areas. Having a range of species makes for more resilient grasslands as at least some species are likely to be adapted to the prevailing conditions. If there are just one or a few species in a sward then there will be less flexibility and resilience.

What do well-managed species-rich pastures and meadows look like?

How can I maintain, improve or restore my species-rich grassland?

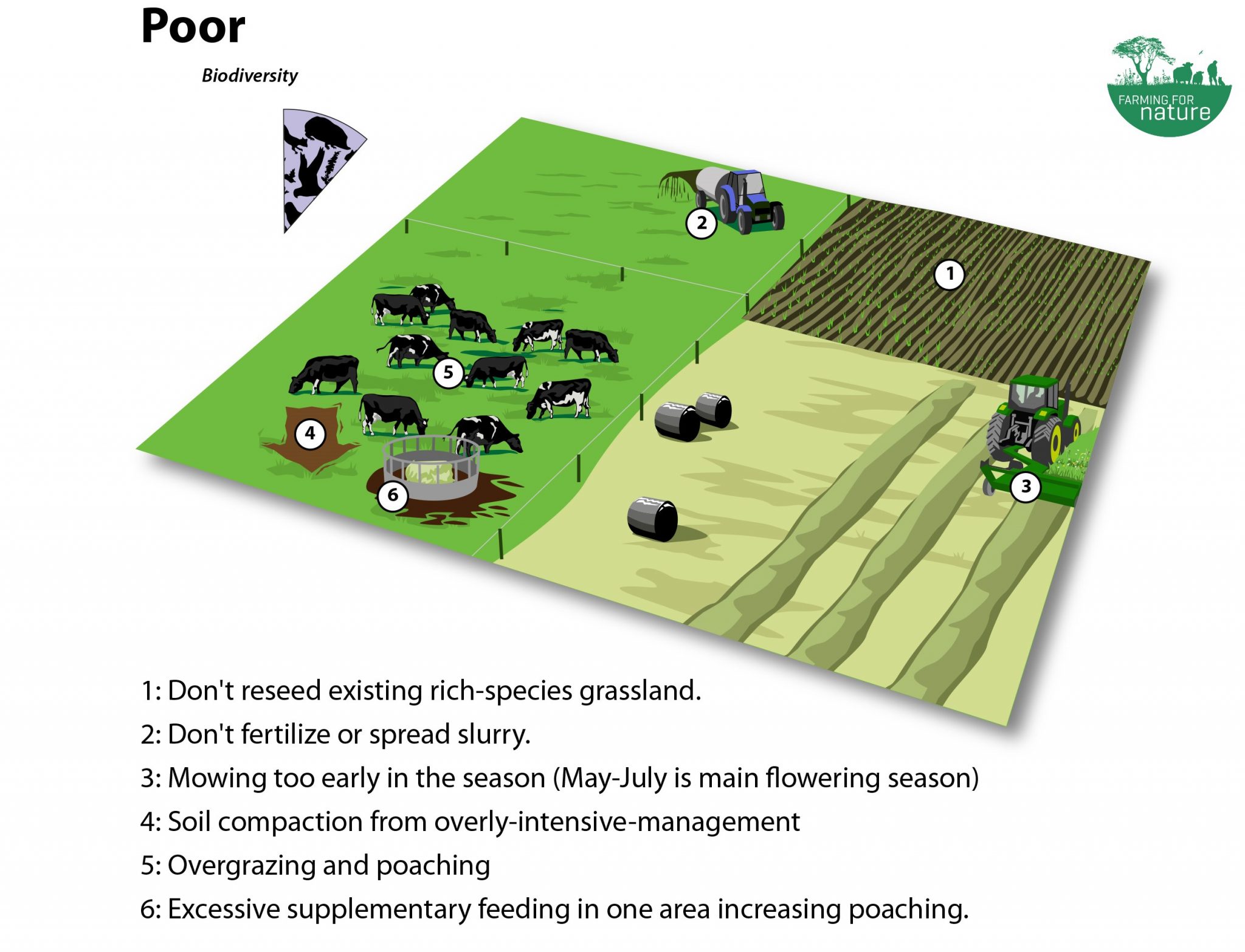

- Start by having a look at the current condition of your pastures (grazed areas) and meadows (areas cut for hay/silage) and what wildlife they support throughout the year. The summer months (May- August) are a great time to look out for a diversity of flowering plants which will help reveal your most species-rich grasslands. The most important thing you can do is retain existing species-rich grasslands – don’t reseed or fertilise them, just keep doing what you did to create and sustain them in the first place!

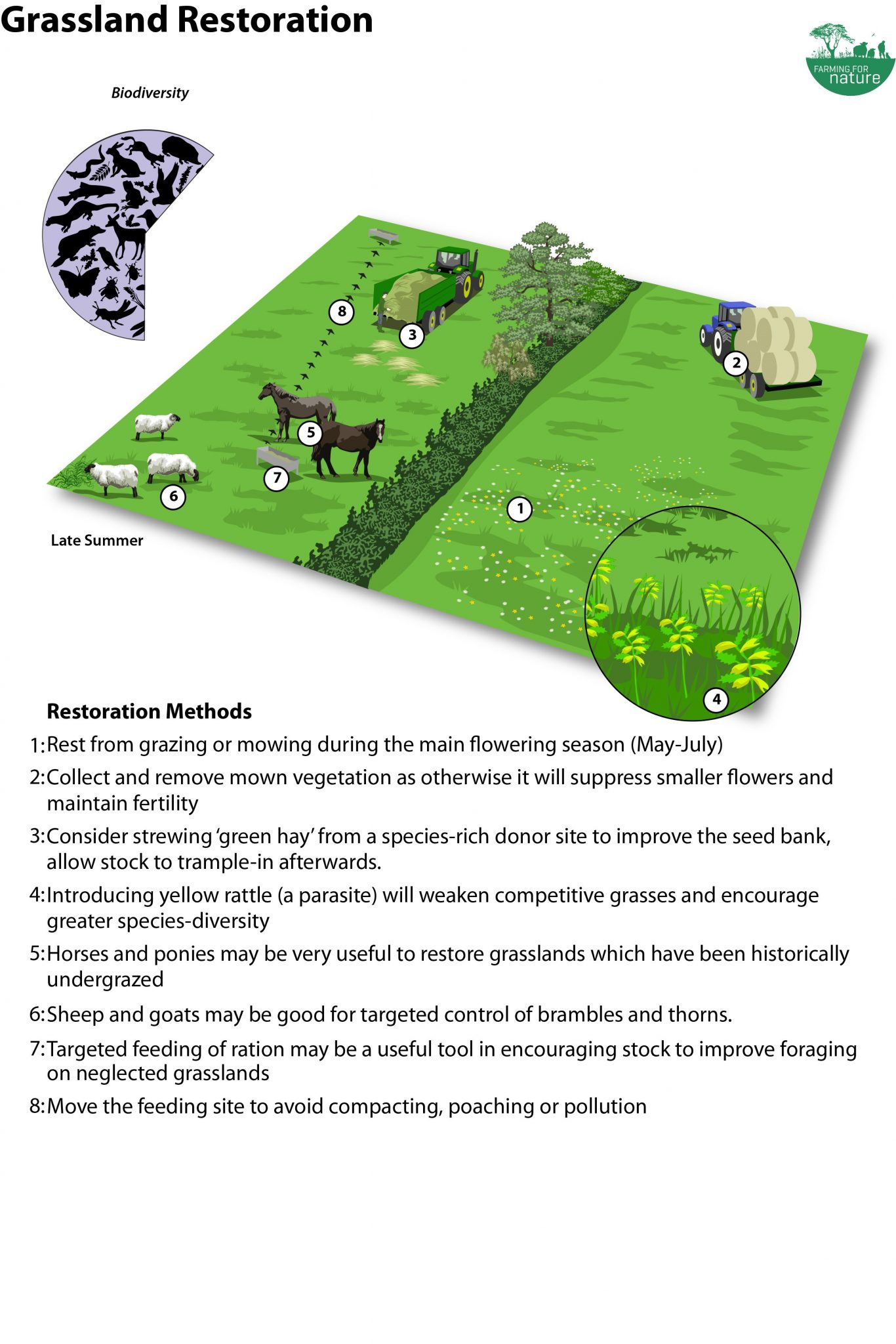

- Natural regeneration and healthy growth in a species-rich natural grassland is best when these areas have not recently received artificial fertilizers or slurry. If a field has been heavily fertilised over a number of years, you won’t get a species-rich sward again anytime soon, so be sure to begin with the fields that have the most potential. Not every field will be species-rich – that’s fine, some may be required for more intensive production or summer grazing. But there may be certain fields, or sections thereof, that can be nurtured.

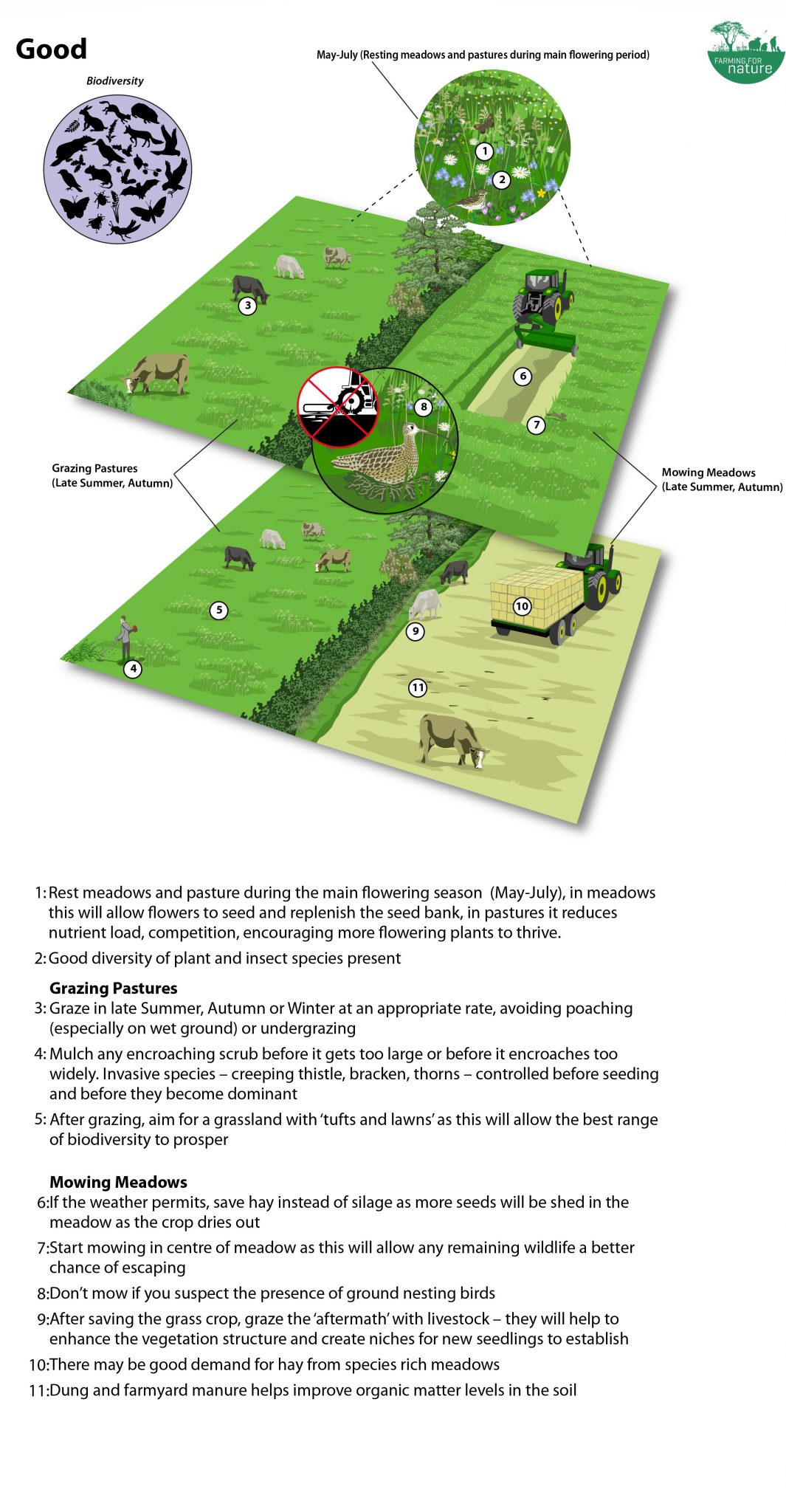

- Whether grazing (pastures) or mowing (meadows), golden rule number one is to try to ‘rest’ these species-rich areas during the main flowering season which is generally May to July. This allows plants to flower and set seed, resulting in a more diverse and colourful sward and a healthy, replenished seed back.

- Golden rule number two is to try to reduce the nutrient load of these grasslands and the best way to do this is to harvest off as much of the vegetation as possible after the flowering season, either by mowing and baling, and/or by grazing with livestock. This will reduce competition for smaller herbs and reduce nutrient levels, meaning more herbs can thrive compared with a sward dominated by more competitive plants.

- If you reduce management too much and don’t harvest off the vegetation sufficiently, it will begin to lodge and form a mat; this makes it difficult for smaller plants to push through in Spring. Instead, species such as bracken, bramble, heather and scrub (blackthorn) may start to encroach – while of value in their own right, these species will, if neglected, ultimately reduce species diversity in your grassland.

- If there is not an existing seed bank, seeds can be brought in by hay-strewing from a species-rich ‘donor’ site, feeding species-rich hay to stock on the site in Autumn/Winter, or planting in sods of soil and plants to stimulate colonisation (after you have reduced soil fertility). Adding yellow rattle – known as the ‘meadow-maker’ (which is a ‘parasite’ on grasses) – to swards will reduce the dominance of the more competitive grasses, and thus encourage more wildflowers.

| Examples of species-rich grasslands include:

Wet grassland: This can be a common and extensive semi-natural grassland type in Ireland. The typically host abundant rushes (particularly soft rush), and also forget-me-nots, ragged robin and, if orchids are present, they are indicative of low soil fertility and low-intensity management history. Birds such as curlew, which are suffering large declines in population, may nest in these grasslands Calcareous grassland: This is dry grassland found in areas with a limestone geology (like The Burren), can be exceptionally flower-rich, and are a particularly good habitat for orchids. Molinia grassland: This is a less common type of wet grassland. It supports a wide range of flowers, some purple moor grass (‘Molinia’), and when well-managed can attract the rare marsh fritillary butterfly that relies on the purple-flowered devil’s bit scabious. Hay meadow: These grassland areas can be wet or dry, but are managed by mowing, typically one late summer cut. This is now a very rare habitat. When in full bloom there are dog daisies, common knapweed, yellow rattle, vetches, yarrow and many more – a wide variety of species and colours. Acid grassland: Generally found in upland acidic areas, they support mat-grass, sheep’s-fescue and sedges, whilst mosses and liverworts can be abundant too. |

Management through grazing (pastures)

- Achieving the right level of grazing, at the right time of year, will provide a patchwork of different pasture heights and structure, offering insects, birds, butterflies and other wildlife plenty of opportunities for shelter and food.

- Tailor your grazing regime to the type of grassland, keep observing, recording and adapting until you get the balance right. On wet grassland, overgrazing will lead to compaction and poaching, on dry grassland undergrazing will encourage the growth of scrub. Aim for a stocking rate which will clear out most of the vegetation without poaching soils or without allowing scrub to encroach – a diverse open sward with ‘tufts and lawns’ is a good outcome to aim for, post-grazing. This may take a lot of trial and error to accomplish – don’t be too prescriptive as external factors such as weather, animal disease etc may strongly influence your management year on year.

- Horses and ponies may be very useful to restore grasslands which have been historically undergrazed. Sheep and goats may be good for controlling brambles and thorns. Cattle are generally very good conservation grazers: while some people prefer to use traditional or native breeds, most breeds can do a good job once they are familiar with the terrain. Supplementary feeding may be necessary on some grasslands, especially over winter: targeted feeding of ration may be a useful tool in encouraging stock to improve foraging on neglected grasslands as the protein in the ration will enable stock to digest more of the rough forage.

- While species-rich grasslands should ideally be allowed flower and set seed without excessive disturbance, some wet grasslands may need light summer grazing as stock would otherwise be more likely to poach it during wetter conditions. Likewise, grasslands dominated by purple moor-grass may need early summer grazing when this grass is at its most palatable (an early bite). But if summer grazing is needed, keep it light!

Management through mowing (meadows)

- Mowing is a useful management tool where stock aren’t readily available, but only if the ground is suitable (not too rocky, hilly or wet for example). There is usually a good demand for hay from species-rich meadows.

- Allow the meadow to mature and seed heads to form before cutting for hay or silage – this may be in mid- to late- July or into August. If you suspect there are ground nesting birds in your meadow (such as the meadow pipit or curlew), you should delay mowing as late as possible. However, if you have to cut the meadow earlier due to weather or other circumstances, it’s more important than ever to resume cutting later in the season in further years as repeated early cutting will deplete the seed bank over time.

- If you have a few meadows on the farm, consider staggering your cutting over a few days to avoid too much disturbance to the wildlife. Mowing from the centre of the meadow outwards allows wildlife the chance to move away from the mowing and into adjacent areas. Leaving an uncut strip along the field margins provides a refuge for wildlife – aftermath grazing will control these areas.

- Aftergraze your meadow with cattle, horses or sheep to enhance the vegetation structure for wildlife. Grazing can help produce a varied sward structure and introduces dung into the field, which brings additional organic matter, nutrients and insects. Grazers may also be able to access parts of the field where mowing is not possible. Light poaching by stock will also create small patches of bare-ground for new seeds to take hold.

- Keep an eye out for encroaching scrub, bramble, bracken or rushes. While these native species are valuable, if unchecked they will reduce the plant species diversity of your grassland. Controlling encroaching species when younger helps avoid having to do a bigger job in the future which might have greater impact on the soil. Never control scrub during the bird nesting season. Hand cutting or mulching scrub is preferable to getting heavy machinery (compaction!) or using chemicals. Never burn gorse/furze as this encourages the seeds to pop and spread. Rushes can be topped late (after the end of August) in the season but watch out for ground-nesting birds. Bracken should be ‘bruised’ (use a harrow for example) when the fronds begin to unfurl (early June) and again 6-8 weeks later.

Avoid

- Avoid management extremes – abandonment or intensification – if you want a species-rich grassland. Avoid grazing or mowing too early in the season (May-July) as this can reduce wildflower species diversity through reduced seed formation and increased cover of grasses.

- Avoid overgrazing or excessive poaching – this will help keep problematic weeds at bay as there will be less open space for them to colonise. This can be done by reducing stocking density or extending rest times between grazing to allow grasslands to recover. Avoid using heavy machinery or heavy stocking during or after wet weather – this compacts the soil and damages its structure, making it more prone to waterlogging.

- Avoid NPK fertilizers, slurry or pesticide use as this will dramatically reduce plant species biodiversity. It will also encourage the growth of more vigorous grasses that smaller, specialised herbs can’t compete with.

- Minimise supplementary feeding as it may introduce nutrients and seeds of agricultural weeds. If you do outwinter and need to supplementary feed, consider feeding species-rich hay or concentrates instead of silage. Regularly move feed points to avoid poaching of the land and further damage to the species richness.